Generative AI is triggering immediate fears about what AI holds for politics, building on the reoccurring collision of technology with campaigning and governing: Trump, Facebook, Russia, Cambridge Analytica, filter bubbles, misinformation, and more. For GenAI, likely impact runs across two main areas:

Deep-faked misinformation, and

A perfect persuasion weapon driven by AI — called ‘persuadobots’ here for short

But will there be, as Sam Altman describes, “personalized 1:1 persuasion” worthy of a being “nervous”? Will there be “adaptive misinformation that can emotionally manipulate and convince even savvy voters and consumers,” as Mustafa Suleyman, the co-founder of Google’s DeepMind AI Lab, describes?

Will it be a system that inserts a 6-second pre-roll ad about paid family leave for an expecting parent, one about transgressive library books for a MAGA acolyte, one about pot holes for Michiganders, and so on? Will they talk about your kids, books you’ve read, and roads you’ve driven on?

Will they trick you? Can it be weaponized as a system to form an advantage for one political party? AI leaders like Altman and Suleyman are worried.

Fear of technology isn’t new. Television brought an emphasis on ‘image’ instead of substance. Social media brought a lot of destabilizing change. That AI is next up isn’t ridiculous. Will it happen, though? I’ve spent the past five years working at the bleeding edge of political and commercial digital advertising and machine learning, and the last few months on on AI Political Pulse, chronicling the evolution of AI politics and policy. As the election cycle gears up, it’s a good time to examine this question:

Are the persuadobots coming to cheat your favored candidate out of a win or is it a nothingburger?

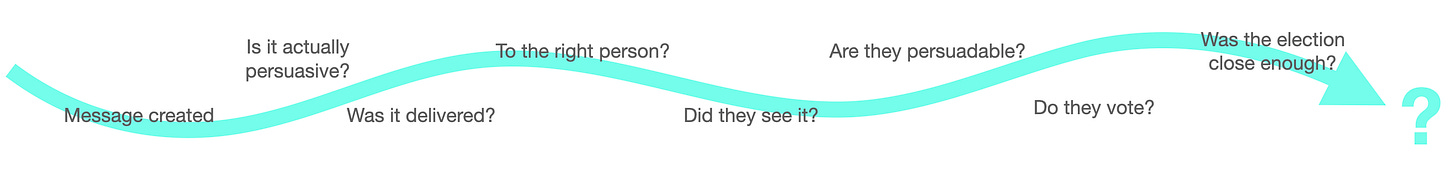

To answer, let’s walk step-by-step through the “value chain” of political persuasion — from who’s listening, to what might work, and then how it gets delivered.

Which voters are persuadable and how many are there?

Political professionals break down the electorate across two axes: if you’ll vote at all, and who you’ll vote for. These two combine to produce two main segments targeted by campaigns:

“Mobilization” targets: Voters who would vote for your candidate, but may not actually show up without an intervention.

“Persuasion” targets: Voters who will probably vote, but don’t know enough about the candidates yet to have a strong preference.

Some academics estimate that the persuadable portion of the electorate is only 7-9%. Why so few? If you vote regularly, you probably pay attention to politics, and if you pay attention to politics, there’s less room for new information to impact your choices, and that makes persuasion difficult. In one study, the net effect of all political advertising was determined to be a half percentage point, which would move vote choice from 50.0% to 50.5%. Another found the effects of political persuasion efforts, especially in high-profile elections, to be minimal. Still, the accumulation of all this effort matters.

In 2020, Biden won Georgia by 0.2 percentage points. State legislative elections regularly come down to hundreds or even tens of votes. An improved persuasion mechanism would be very important.

What do we know about persuasion itself?

Political message testing firms have performed thousands of persuasion ad tests in controlled digital survey environments. It’s not perfect, but it’s the best we have. Some trends have emerged:

The average persuasiveness of an ad is about one percentage point. (If everyone saw and internalized it, a candidate’s vote share would go from 50% to 51%.)

There’s wild variance in the persuasiveness of messages that is difficult to predict. Contexts shift from election to election. Some ads outperform significantly outperform the averages. Many backfire. Academics looking for patterns in why this happens have not found any yet.

Persuasion is generally more effective in lesser-known elections. Providing specific bits of new information help voters update their existing knowledge. (By October 2020, it was nearly impossible to convince anyone of anything new about Trump.)

These tests also happen in controlled situations. As a San Francisco resident, my mailbox fills up every election cycle with voter guides, mailers, and sample ballots — thrown away immediately.

Is there value to personalizing persuasion?

“Facebook must be listening to me, otherwise how did it know I was thinking about that new dining table?”

Despite the meme, Meta has never needed to listen to your conversations. (Think of the battery life consumption!) There’s enough signal that comes from being a millennial male located in San Francisco, having bought certain products, that advertisers don’t actually need to know my name or too precisely who I am.

Is politics any different? Does personalization have value? It might not.

Recent political science studies find that many messages are universally persuasive, moving opinions across age, gender, and even ideology. Yale Professor Alexander Coppock’s “Persuasion in Parallel” research shows that despite a deeply polarized society, persuasive messages can work across age, gender, race, ethnicity, or party affiliation.

Even with politically-charged issues or written in politically signifying values language, persuasive messaging still works across ideological and demographic splits. Obviously, if a leader a voter trusts has an opposing viewpoint, then voters will factor that in, but it doesn’t totally negate the original message. (Hewitt 2022, Tappin 2023)

An AI that makes it way cheaper to personalize messages could hurt the cause it’s designed to help by steering away from a few central messages that work the best across the population.

How would the AI know what to personalize the message on?

What do we know about what a given voter cares about that might be the setting for their customized persuasion message? Very little. Only a small number of people donate, or sign up for petitions, or perform other specific actions. Everything else is inferred via surveys.

Accurate polling is famously tough these days, and generative AI doesn’t fix that. You can infer what they might care about based on demographic attributes, but as the literature indicates, that may not be that useful in many cases.

Still, a generative AI may be able to develop messages for new sub-segments of the population based on reinforcement from survey responses, but given the challenges mentioned above, this is likely to be only a stepwise improvement on the status quo.

Can the system deliver the message to the right voter?

Turning to the mechanics of mass media, to personalize, you need two things:

Individually-addressable media

To be talking to the right person

Many of the most popular and well-studied political media methods are not easily 1:1 individually addressable, including broadcast/cable television, Meta, YouTube, and radio. Available are text messaging, direct mail, in-person canvassing, and some programmatic digital advertising.

On the “right person” question, phone numbers are often wrong, digital “match rates” lead to not finding sometimes >30% of your target, and many platforms have simply disabled many individual targeting features for political advertisers, like YouTube.

Even magically effective persuasion messages will get heavily diluted by the time they arrive with voters.

Conclusion and Remedies

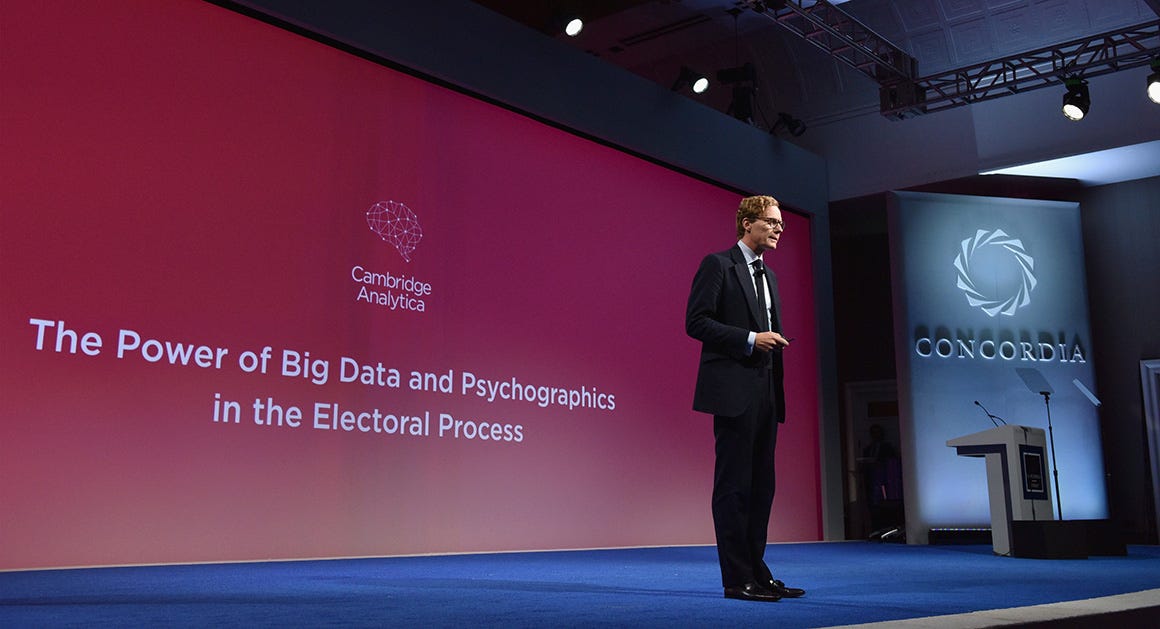

Like Cambridge Analytica, the fear over AI Persuadobots is looking to be overwrought. The maximum threat area is probably downballot elections. AI could make it inexpensive to create localized content, with reinforcement feedback driven by surveys, ad delivery, and ad engagement data. (Extended out, this does start to sound like reinforcement learning from human feedback.)

However, these elections are not where the vast majority of political resources go, and it’s unlikely a complex and expensive system like this would get created for it to not work in the elections that most people care about. What should we do to close the possibility of a downballot edge case opening up? Besides liking and subscribing to AI Political Pulse to track how this space evolves, there’s room for:

Internet platforms to embrace mandatory disclosures and watermarks of AI-generated content

Government regulation via the FEC or other entities to mandate disclosure of AI-generated content

Follow-on or leading legislation from states to avoid creating state-level disclosure loopholes.

Many of the obstacles to productionizing persuasion at scale or even spreading deep fakes throughout the Internet come down to Internet platform decisions, like Google’s ban on targeting individual lists of voters or TikTok banning political ads. Those come with some disenfranchisement for individual campaigns, but in the AI era are likely newly worth the cost. Deep fakes are a much more real threat, and the public and leaders like Altman and Suleyman would be wise to focus on those. When content spreads like wildfire through organic social media, private group chats, or other channels, it comes with trusted messengers, no need to pay for distribution, and much less moderation. That is, if the platforms keep it that way.

Thanks to Jessica Alter, Gina Pak and Alex Lindsay for feedback on this post.